This survey is inspired and supported by the Dora Factory team during the research into practical ABFT implementations on orbital communication and computation systems.

In an asynchronous environment, there is no bounded time for a message sent from one to another. In this article, we survey the family of asynchronous BFT consensus protocols, analyze security and performance of several important protocols.

Introduction of blockchain as a distributed system

In this article, we will go through the family of Asynchronous Byzantine Fault Tolerant (ABFT) consensus in blockchain systems. So let's briefly (re)-introduce blockchain.

A transaction-based state machine

As a state machine, a blockchain system stores the complete states for multiple objects (expressed by addresses) from the beginning time (birth of the objects in the system) to the present. The system also stores deterministic logics (e.g. encapsulated in smart contracts) that can be invoked by transactions.

Transactions are the inputs of the system. Each transaction encapsulates a set of data. The data can be logics, addresses, or state data that has been recorded in the system before. Each transaction is sent to the system to invoke one or more certain logics that have been deployed in the system. The contents of the transaction are treated as inputs to the certain logics to be invoked. After that, the system exports a set of outputs that will be regarded as the new states. The transition process can be described by the following equation:

where

Next, we should identify the actors in the system.

The actors of the system

Nodes. We assume the system (blockchain) has

Users. Participants of the system. Each user is an object with a unique identity (address), although in reality a user often has more than one identity in the system.

Consensus protocol. Conceptually, consensus protocol is a set of ordered instructions that stipulate the behaviors of every honest node. In order to keep the system secure and high-performant, we must figure out how to coordinate the nodes via consensus protocols.

The assumptions of an asynchronous system

In an asynchronous network, we must assume:

- Asynchrony. there is no bounded time for a message sent from one to another;

- Unforgeability. if a node sends a message to another it connects, no one can modify the message.

- Termination. if a message has been sent from one to another, the another will eventually receive this message.

The three assumptions are crucial to guide us to construct an ABFT consensus in an asynchronous environment. (1) is the main assumption of ABFT protocols, a property that differentiates ABFT from other BFT protocols; (2) is easy to achieve through asymmetric cryptographic technologies such as digital signatures; (3) is an assumption that corresponds to an asynchronous environment. We will see that without this assumption, it's going to be very hard to construct a feasible ABFT consensus protocol.

One more (advanced) assumption

- Adaptive adversary: An adaptive adversary is not restricted to choose which parties to corrupt at the beginning of an execution, but is free to corrupt (up to

) parties during a consensus process.

Some important metrics

- Quality: the probability that the decision value was proposed by an honest node.

Here, "propose or proposed" means the opinion of a node to an object.

- Asymptotically optimal time: if Byzantine Agreement is solved using an expected O(1) running time, we say asymptotically optimal time.

expected O(1) means 1) only one instance is operated; and 2) the instance can terminate within certain steps with overwhelming probability.

- Asymptotically optimal word communication: An ABFT consensus protocol solves Byzantine agreement using an expected

message and each message contains just a single word where we assume a word contains a constant number of signatures and domain values.

The goals of the system

For security, we must guarantee:

- (1) the inputs of the system must be verifiable and only the inputs that are verified as valid will be accepted by the system;

- (2) the logics that are invoked by the inputs are executed correctly.

- (3) if (1) and (2) hold, all honest nodes in the system must output the outputs of (2).

- (4) the system must guarantee liveness, i.e., as long as a correct input has been sent by a user to an honest node of the system, the input will be eventually executed to export its output (new state).

Actually, (1) is not explicitly emphasized in current ABFT consensus. However, (1) is important to let honest nodes to only send valid messages to others at the beginning of executing an ABFT consensus protocol.

(2) responds to the execution of smart contracts or the instructions defined by an ABFT consensus protocol.

(3) emphasizes the consistency, i.e., every node has the same view on the corrected outputs. (some paper says (3) as totality property)

(4) signifies the liveness property. It means an unified consensus will be eventually reached by all honest nodes if all of them executes the consensus protocol.

The two properties, consistency and liveness, define the security of the system. Actually, (1), (2), (3) is used to guarantee consistency.

Performance metrics of the system

- Throughput. The number of transactions the system can process at a certain time slot, e.g., 1 seconds, denoted by tps.

- Latency. the duration from the time (a correct transaction sent to an honest node) to the time (the transaction is recorded in the system).

We always hope for high throughput and low latency.

Constraints of a system

Since the system is operated and maintained by its nodes, the hardware bottlenecks of the nodes actually indirectly constrain the performance of the system. Generally, three capacities mainly determine a node's hardware capacity.

-

Processor (CPU): CPU is responsible for performing various computational tasks. In blockchain networks, nodes need to perform tasks such as verifying transactions and processing consensus algorithms, which require the computational power. Powerful CPUs can increase the speed and efficiency of nodes when processing tasks. In general, ABFT consensus assumes the computational capability is enough to all the nodes in the system.

-

Memory: Memory is used to store the programs and data being executed. Blockchain nodes need enough memory to store transaction pools (Txpool), handle consensus algorithms and execute smart contracts, among other tasks. Higher memory capacity and speed can improve the performance and responsiveness of nodes.

-

Bandwidth: Bandwidth refers to the data transmission rate of a network connection and is used to measure the amount of data a node can send and receive per unit of time. Blockchain nodes need to communicate a lot with other nodes, including broadcasting transactions, transmitting blocks and sharing data. Higher bandwidth can increase the speed of communication between nodes, thus improving the performance of the entire network.

Other capacities:

-

Storage: Storage is a persistent storage area of a computer that is used to keep data. Blockchain nodes need to store data for the entire blockchain, including all blocks and transaction records. As the blockchain grows, the storage requirement will also increase. Therefore, nodes need enough storage space to store the data of the entire blockchain.

-

Network Interface: A network interface is a hardware device that connects a computer to an external network, such as an Ethernet card or a wireless network card. Blockchain nodes need a stable and high-speed network interface to stay connected to other nodes for communication and data transfer.

Bandwidth may be the most scarce resource of the system. We assume a node with a least bandwidth capacity has 1000 Mps bandwidth, which means it can upload or download at most 1000/8=125MB data in a second. We assume one transaction has 500 bytes; assume for each second, 50MB are used to receive user's transactions and other node's transactions and 75MB are used to send messages for consensus. On this basis, a node can receive at most

Memory is also critical. Each node must store necessary state data of the system and the transactions received as valid but not yet recorded in the system into its memory. As the system grows, the size of state data will be increased continually. If the size of state data is too large, it will centralize the system.

Computation capacity (CPU/GPU) is also important for the nodes and the system. Since more and more complicated logics have been deployed to blockchains, if a node has poor computation capacity, it will take a long time for transaction verification and logic execution. Other nodes configured with high computation capacity will wait for the low-bounded nodes.

In summary, ABFT consensus is constructed to fully use the hardware capability of the participating nodes in the system to let them efficiently and quickly reach an agreement on a block with the preservation of consistency and liveness.

A naive example

Conceptually, asynchronous Byzantine Fault Tolerant (ABFT) Consensus processes transactions in ordered epoches. one ABFT process is handled in one epoch and each ABFT process can be generally divided into three stages, i.e., transactions collection and block formulation (TCBF), message broadcast, and steps to reach agreement on the broadcasted message. After the process, a block is generated and chained. How does that happen? How is it different from a normal BFT epoch? Let's dive into a complete but naive ABFT epoch.

Stage 1: Transaction collection and block formulation (TCBF)

Each node in the system has a unique terminal that everyone can send messages to it.

- Each node listens, receives and verifies the transactions sent by users or other nodes. Valid transactions will be recorded in the node's local transaction pool (Txpool). The standard of "valid transaction" varies. For example, one common rule is that the signature w.r.t the transaction and its sender must be verified as correct.

- Before the beginning of an epoch, each node should select a certain number of transactions in Txpool and orderly package them into a sub-block. The selection operation can be randomly or deliberately performed by the node. Also, the exact sequence of the transactions in the sub-block depends on the nodes as well.

Generally, the sub-block can be further processed Erasure coding. However for simplicity, we temporarily let it aside. Also, we denote the block formulated by

Stage 2: Byzantine Broadcast

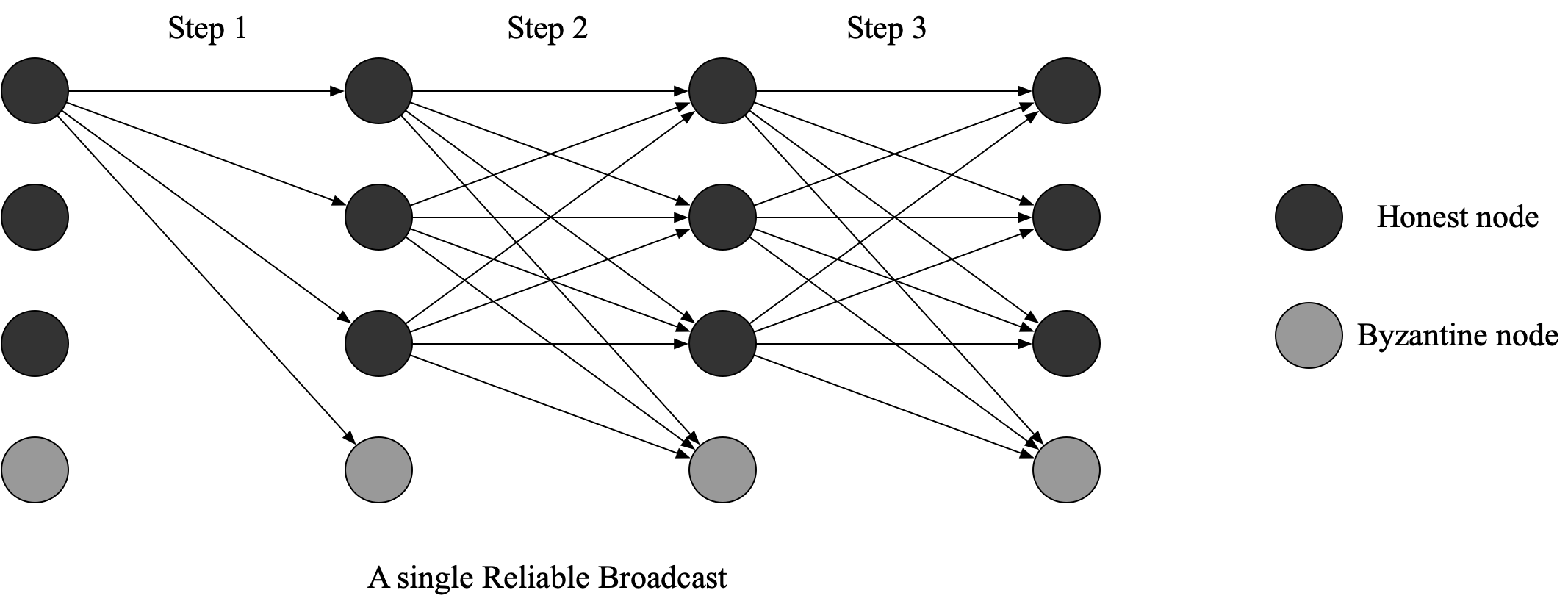

Byzantine Broadcast can be achieved by Reliable Broadcast (RBC). Here, we look at the first RBC protocol.

At the beginning of an ABFT epoch, each node initiates its RBC instance:

broadcast its sub-block (“broadcast”means the message is sent to all the nodes the connects).

After this step, all the nodes will eventually receive. - Once

receives 's sub-block , it directly broadcasts it.

After this step, all the nodes will receivesent by . As a result, each honest node will broadcast once and each node will eventually receive for at least times. - If a node like

receives the same for at least times, it broadcasts . If it receives for at least times and it still has not broadcasted , it broadcasts .

After this step,waits for pieces of . If it receives pieces of , it assures that every honest node will receive pieces of . So it can assure that every honest node will reach an agreement on sub-block . So we say “ delivers ”and ’s RBC instance terminates for .

We must emphasize that receiving

Additionally, if a honest node receives

Since there are

Considering that both

Stage 3. Asynchronous (Byzantine) binary agreement (ABBA or ABA)

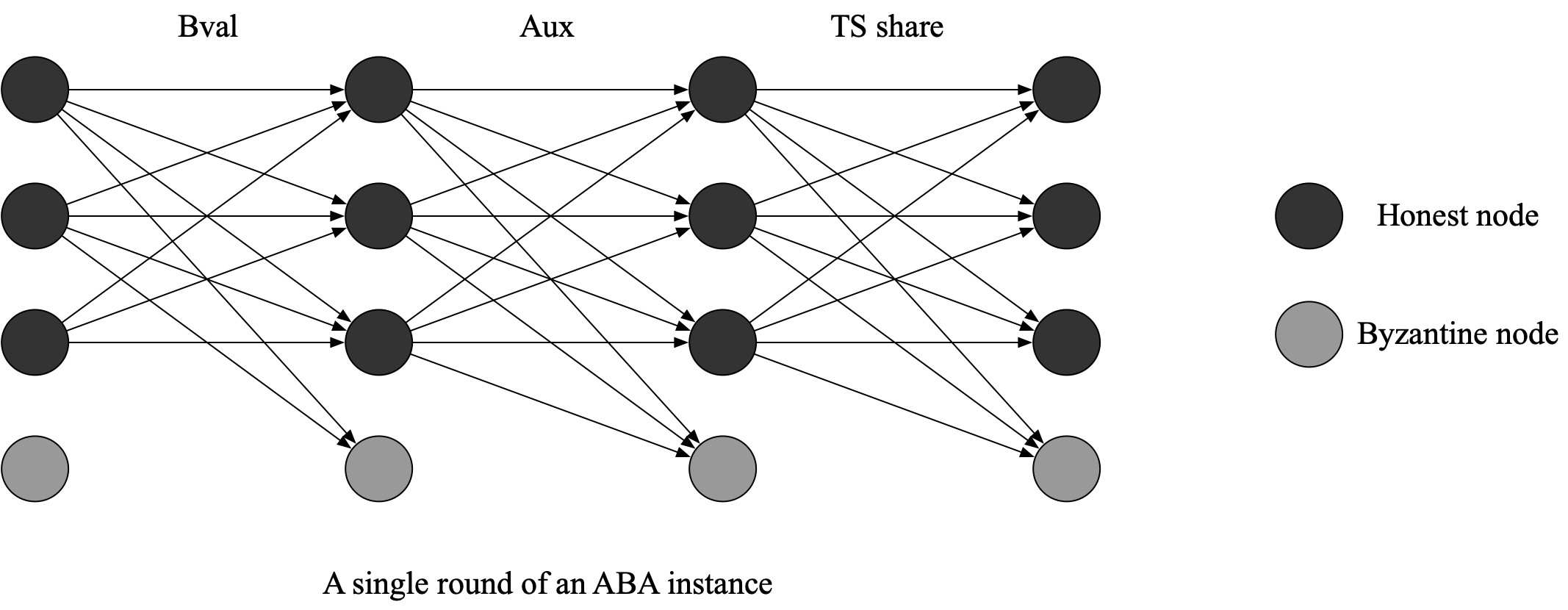

Now we introduce an ABA protocol presented in this paper, which was later used by Honey Badger BFT protocol. There are in total

- At the beginning of

for , from the perspective of , assuming is honest and has entered this stage, if delivered at stage 2, then broadcasts in , where represents the opinion of "agree" on 's RBC instance, and represents . If did not deliver at stage 2, there will have two situations: 1) if has not decided on different ABA instances, does nothing at this moment; 2) if has decided different ABA instances in which is not included, broadcasts in . We will explain the meaning of “decide” shortly. - If

receives the same and it has not broadcasted , it will broadcast . - If

receives the same , and it has not added to a set called , it add to . - When the set of

is not empty, broadcasts . (Apparently, is the value that is the first to add to the set of ). - If

receives valid , it broadcasts its threshold signature shares. (Here, we must emphasize that a “valid ”for means in has been added to ’s ). - if

receives valid threshold signature shares from other nodes, it generates a unique threshold signature . It then calculates or and create a common coin =the first binary number of or . Note that there are three cases:

(1)values from the received valid are the same:

(1.1) If the first binary number ofor is equal to that has been added to ’s , it decides as .

(1.2) otherwise,broadcasts in .

(2) if thevalues from the received valid are not same (i.e., both and are added to and received both and ), broadcasts at .

Repeat untildecides .

Apparently, "decide or decided" here means the node

Protocol Security

Security considerations of Stage 1

At Stage 1, the nodes of the system mainly perform the block formulation operations, i.e., packaging valid transactions from the Txpools into their sub_blocks. Hence, in Stage 1, we should consider whether the node should validate the transactions before it adds them to its sub_block. The validity of a transaction should be carefully defined. Moreover, it is important to prevent censorship attacks - every valid transaction should be included in the blockchain within a certain time slot.

Security analysis on Stage 2

At Stage 2, each node will initiate, progress and complete its RBC instance. In order to make a RBC instance secure, the RBC instance must satisfy the following properties:

- Agreement. If a correct node delivers

, then every node eventually delivers . - Validity. If a correct node

broadcasts correct , then eventually delivers . - Integrity. For any sub_block

, every correct node only delivers at once. Moreover, if a node delivers , then was previously broadcasted by a honest node.

As for validity, because an honest node

As for agreement, if an honest node delivered

Integrity is trivial to prove.

Security risks

An adversary can deliberately delay the communication and increase latency (network latency caused by DDoS attack and so forth) of some honest nodes. On this basis, an adversary can launch an attack to censor some honest node's sub_blocks.

The adversary can first delay some honest nodes’ RBC instances. After that, an honest node may deliver

Based on this attack, the adversary can further let the sub_blocks of Byzantine nodes tain invalid transactions. Due to the mechanism of ABFT protocols, the transactions encapsulated in each sub_block will not be verified until the final block of this epoch is generated. At this time, honest nodes will find some of sub_block's transactions invalid. As a result, those invalid transactions will be deleted from the block.

Since an adversary can at most censor

Security analysis on Stage 3

Similarly, in order to make an ABA instance secure, we require each ABA instance satisfy the following three properties:

- Validity: If all honest nodes propose

for an ABA instance, then any honest node that terminates decides the ABA instance as . - Agreement: If an honest node decides a ABA instance as

, then any honest node that terminates decides the ABA instance as . - Termination: Every honest node eventually decides 0 or 1 for each ABA instance.

- Integrity: No honest node decides twice.

Proving validity is trivial: all honest nodes propose

As for agreement, if an honest node decides

Proving integrity property is trivial since it is impossible for a Byzantine node to simultaneously receive 2f+1

A security glitch

In the naive scheme, termination can be violated in the following scenario:

Assume there are

So every honest node will receive

Some honest nodes (assuming

As long as adversaries let

Performance analysis on the naive example

Performance analysis on Stage 1

Specifically, a node's sub_block contains

Performance analysis on Stage 2

For each RBC instance initiated by an honest node, every node will first broadcast its sub_block. As a result, it incurs

Performance analysis on Stage 3

For each ABA instance, it is bandwidth-oblivious, since each node is only required to broadcast binary numbers and limited bytes. The issue is that ABA instances are time-consuming.

- First, for

, within each round, three ordered time periods exist in each round ( -broadcast, -broadcast and share-broadcast). In each time period, it costs some time for each node to wait for valid , valid and valid shares. - Second, due to the randomization introduced by common coin, no one can make sure which round will be the last round for the

instance. So several rounds (generally 2 or 3 rounds) will be executed. - Lastly, since

instances are concurrently operated, the time when Stage 3 terminates depends on the slowest instance.

Specifically, as for communication cost, only

Performance analysis after Stage 3

After Stage 3, each node suffers a huge computation overhead, i.e., checking invalid transactions, deleting repeated transactions, computing each transaction's computation tasks to generate new states, and formulating the final block.

In order to execute transactions, each node should store necessary state data in their memory. As the states continuously increase, how to mitigate the memory overhead for each node deserves extensive research.

The state-of-the-art improvements on ABFT protocols

Stage 1 improvement

There is a lack of concern on improving performance and security of Stage 1. Most ABFT consensus protocols are in research labs, and real-world adoption is rare. However, Stage 1 is quite important when a network actually runs on ABFT consensus.

As a survey, we will skip this part and come back later to discuss implementation details.

Stage 2 improvements

Improve the performance of RBC instances

There are several ideas proposed to improve RBC security and performance.

Verifiable Information Dispersal (VID) is a proposal to replace RBC. For a VID instance such as

divides its sub_block into pieces and uses erasure-coding to encode the pieces to pieces. Each piece can be denoted as , where . broadcasts to . - When

receives , does not broadcast . Instead, broadcasts , which is much more bandwidth-saving. Therefore, each honest node eventually will receive at least pieces of the same w.r.t ’s instance. - If a node has received

pieces of the same w.r.t instance, it broadcasts (same as RBC instance). - If a node has received

pieces of and it does not broadcast , it broadcasts .

As for the leader of

As for the followers for

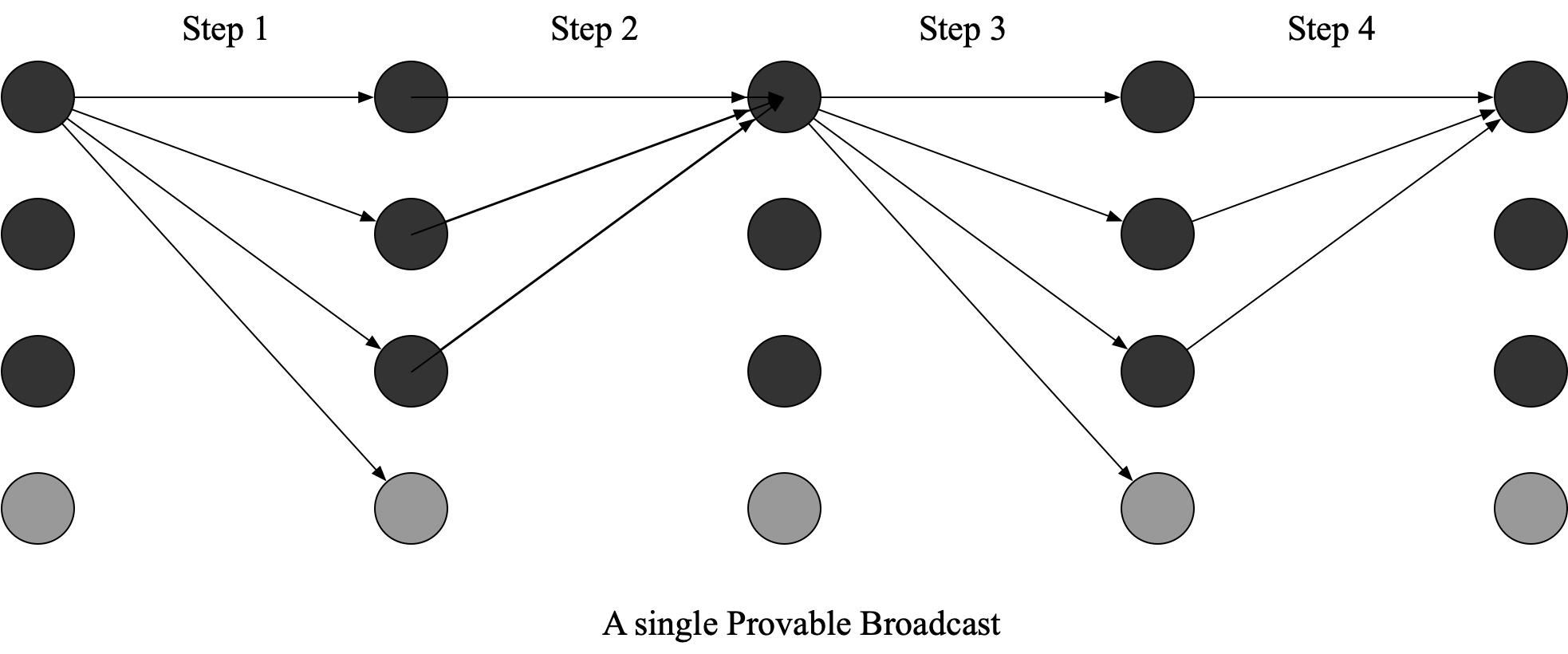

Another idea is to use provable dispersal (PD) instances to replace RBC instances. For a PD instance

first broadcasts (same as RBC instance but contents are different). - The difference is that when

receives , verifies the cryptographic commitment using proof . If verified as valid, generates a threshold signature shares and sends only to . - After 1 and 2, an honest node

will finally receive at least different but valid signature shares from distinct honest nodes. Based on that, can generate a valid threshold signature . Then, broadcasts . - after receiving

, checks the validity of . If it is verified as valid, sends its threshold signature share $\sigma’{i} node{k}$. - after receiving

valid , it generates .

As for the leader of

For a

The difference of the above two schemes is that the former relies on strong validity, i.e.,

The tricky part of the above two schemes is that each

We have to further divide a RBC instance into two parts - a VID or a PD instance and a retrieval phase. Most importantly, the retrieval phase can be executed at any time for a node. Retrieval phase is set to recover

When

The core merit of such design can significantly improve system throughput due to 3 reasons:

- Once

VID or PD instances are completed, a node can enter ABA instances. - VID/PD instances and ABA instances are bandwidth-saving.

- The bandwidth-consuming retrieval phase can be processed throughout the whole ABFT consensus process.

- As for 1, Since the bandwidth capacity of each node is different, if an honest node's bandwidth capacity is relatively lower than others, it will cost much more time to finish

bandwidth-consuming RBC instances. consequently, the node's ABA instance will be delayed. Since a complete ABFT process requires all the honest nodes finish their ABA instances, the node with lowest bandwidth capacity will decelerate the whole ABFT consensus process. Therefore, if each node only requires to participate in bandwidth-saving VID instances, even if there are nodes with lowest bandwidth capacity, they might be able to use the same time to finish their bandwidth-saving VID instances. - As for 2, VID or PD and ABA instances are much more bandwidth-saving than RBC instance and retrieval phase. Specifically, In VID or PD instance, apart from broadcasting

or by each node for once, each node only requires to broadcast or . (Note that in an ABA instance, each node only requires to broadcast binary numbers and threshold signature's shares; ABA instance and its alternatives will be presented in detail later). In contrast, in an RBC instance, each node is required to broadcast fragments of all the received sub_blocks (at least receiving fragments). In other words, as for a node in RBC stage, it will broadcast at least $n*b+(2f+1)b nb$ sub_blocks. - As for 3, since bandwidth-consuming retrieval phase can be conducted by nodes throughout the whole ABFT process, each node can fully use their bandwidth throughout the time. Compared to the previous RBC+ABA scheme, all the bandwidth-consuming tasks are processed in the RBC stage. However, in the ABA stage, the node's bandwidth are being idle. As a result, the nodes cannot fully use their hardware capacity. Using this method, each node's hardware capacity can be fully utilized.

Solutions on retaining honest node's sub_blocks

In the security analysis of Stage 2, we have identified that some honest node's sub_blocks can be censored by an adversary. There are some ways to tackle this issue.

DispersedLedger proposes something interesting. The protocol requires each node to locally manage a

For example, we assume the current time is the beginning of

Now, the current time is the beginning of

Also,

Thereafter, in each epoch, each node will package the information of its locally managed array into its sub_block. After that, each node will eventually acquire at least

For example, at the beginning of

However, this design introduces an extra issue on node's memory capacity, that is, each node should maintain every unfinished RBC/VID/PD instance. Note that maintaining these broadcasting instances is memory-consuming, since all the received information related to the instances cannot be discarded if the instances are not completed. Consequently, an honest node may simultaneously maintain the number of instances much larger than

There is a strategy to deal with the memory issue. It uses a PD instance to broadcast each node's sub_block. More efficiently, when a PD instance is completed, the next PD instance can be immediately initiated, which is very different from the current RBC schemes (when a RBC instance of a node is completed, the node can only initiate the next instance after the current epoch is over). In this strategy, some nodes may receive more than one PD instance owned by the same node within one epoch.

Similarly, each node should also locally keep an

Furthermore, in order to not keep all the unfinished PD instance in memory, each node can (i) directly keep the finished instance in consistent storage immediately; and (ii) do not keep the unfinished PD instance in memory if the series number of the PD instance is far (such as

Improvement on Stage 3

There are several ideas that can improve the ABA stage of ABFT.

Double Synchronized Binary-value Broadcast introduces several phases to the ABA process: the BV phase and the agreement phase.

BV phase (Same as the first step in the naïve example of stage 3). From the perspective of

- If

receives its input on , it broadcasts . - If

receives on sent by different nodes, if it has not broadcasted , it broadcasts . Note that and is not equal to its input . - If

receives and/or from distinct nodes, it records and/or in .

Agreement phase:

- If

's is not empty, it broadcasts where . - If

receives other nodes' and , it records in . - If

records in and those is from distinct nodes: - If the

is the same binary number, output as the . - If there is no

the same binary number in , it outputs any binary value of .

Actually, in

BV phase + agreement phase is equivalent to the SBV protocol.

After the first SBV phase is completed:

- If

's contains the same , it continues to broadcast and . - Otherwise, it broadcasts

. - if the node who broadcasts

receives , it broadcasts . - if the node that broadcasts

first receives , it broadcasts . - if the node who broadcasts

first receives , it broadcasts .

So, after the second SBV, no one will receive

After the second SBV,

- if the node receives

, it broadcasts its threshold signature share. And if the node receives valid signature shares, it generates the threshold signature and then generates a common coin . If , it decides the ABA instance as ; otherwise, it broadcasts . - if the node receive

, where * can be and . It broadcasts its threshold signature share. And if the node receives valid signature shares, it generates the threshold signature and then generates a common coin . After that, it broadcasts . - if the node receive

, It broadcasts its threshold signature share. And if the node receives valid signature shares, it generates the threshold signature and then generates a common coin . After that, it broadcasts .

Repeat the above procedure until termination.

This ABA instance solves the termination problem shown from the naive example.

Claim: After the first SBV, if there is an honest node broadcast

Proof: if there is an honest node broadcast

Claim: During the second SBV, no honest node will add

Proof: During the second SBV, only Byzantine nodes could broadcast

During the second SBV, an honest node could only broadcast

After all, at the end of second SBV, there are only three possibilities:

- (1) an honest node receives

valid ; - (2) an honest node receives

valid ; - (3) an honest node receives

valid , where * can be or .

Claim: (1) and (2) cannot exist at the same time.

Proof: if an honest node receives

Then if all honest nodes receives

- if honest nodes either receives valid

or receives , all honest nodes will eventually decide for this ABA instance. - if honest nodes either receives valid

or receives , all honest nodes will eventually decide for this ABA instance. As long as in a round, is equal to , all honest node will eventually decide for this ABA instance. - if all honest nodes receives

valid , all honest node will eventually decide for this ABA instance.

Performance: communication and message cost in this scheme is similar to the naive protocol. However, this one takes more steps (5 to 7 steps) for each round (2 or 3 step for each SBV and 1 step for generating

Pisa is another protocol from the PACE ABFT framework that replaces ABA with reproposable ABA (RABA). Here is how it works differently compared to the previous ABA protocols:

- if an honest node delivers

, the node directly broadcasts , and . - if an honest node that broadcasts

receives broadcast , it directly broadcasts , and . - if an honest node that broadcasts

, and it receives or broadcast before it receives , it directly broadcasts . - if an honest node that broadcasts

receives , it generates and broadcasts . - if an honest node broadcasts

firstly, it then deliver , no matter what rounds it locates, it repropose , and .

In the worst case, Pisa has a similar performance with DSBV. However, in the other cases, it performs better than the current ABA schemes.

The worst case is that no more than

There are also other improved protocols for ABA. Speeding Dumbo designs a leader election protocol to replace ABA protocol after RBC or PD stage finishes. Tyler Crain's paper, in contrast, devises a more efficient ABA instance using threshold signature schemes multiple times. Readers are highly recommended to read these papers on ABA alternatives.