The Hacker Movement

The world’s first hackathon was reportedly organized in 1997 by a group of Canadian cryptographic developers, 20 years after Donald Knuth released one of the world’s first open source software TeX.

In 2003, Paul Graham pointed out in his “Hackers and Painters” that hackers were often confused in a computer science department because they were taught to write research papers while they really wanted to build beautiful things (software).

So, what is a hacker? It can be best characterized by Eric Raymond’s hacker ethos in his article “How To Become A Hacker” (2003).

- The world is full of fascinating problems waiting to be solved.

- No problem should ever have to be solved twice.

- Boredom and drudgery are evil.

- Freedom is good.

- Attitude is no substitute for competence.

This is a quite different approach — while schools and universities teach people to learn something then probably build something, hackers identify problems and build to solve the problems first. They learn necessary techniques while building the solution.

The drastically different approaches led to a different way to deal with problems. While most people followed the school tautology that “if you want to build something, you need to learn everything underneath it”. The attitude changed since then, and there was a great awakening among the developer community. The hacker spirit was widely accepted, and the hacker movement was spawned.

The hacker movement really took off when open source software started to grow tremendously.

There was a linkage between the open source / free software movement and the hacker movement. If someone wants to “hack” something and solve a problem by her own, she must be able to focus on the problems and take whatever available to tackle the problem itself. There is no time for a hacker to reinvent a wheel — a hacker utilizes whatever that is available to solve the problem. If there was no open source software widely available, it would be difficult for many to become hackers when intellectual properties are controlled by big companies. An obvious example of our time is — if Bitcoin was not open source (or even worse if the technology had been “patented”), the founding team of Ethereum would have a really hard time to even start the project, then the world would lack a lot of creativity and fun.

Coordination was also important. In the early 2000s, people were still passing around flash drives containing git repos or building local networks for code version control. The creation of GitHub was important to the open source community. GitHub invented a standard workflow of remote git repository collaboration, and a platform for sharing open source software globally. With the rapid growth of GitHub (and other platforms like GitLab), software around the world became accessible to everyone, and developers across the globe can work together on the same repos without any geographical barrier.

By early 2010s, the open source tech stacks had become more sophisticated and well-adopted than the close-sourced tech stacks in many fields. In the then- Silicon Valley, most startup companies started to heavily rely on open source tech stacks. Big companies were building their own open source software or supporting open source repos they feel are strategic to their business.

The widely available open source tech stack also gave opportunities to university students, community developers, and startup engineers to learn, contribute and build. With open source software, developers could build without permissions from big companies. They can learn by themselves, build impactful technologies and products by themselves, the era of permissionless innovation started.

The idea of becoming a “hacker” in Eric Raymond’s book came true, and a global hacker movement took off.

The Development of Global Hackathons

A hackathon movement took off around 2010 in US universities. The first wave of hackathons were organized in universities around 2010. In 2013, MHacks became one of the largest university hackathon organizers among others (PennApps, CalHacks, HackMIT, and so on), attracting more than 1000 hackers to attend in a single event. Students who attended these hackathons were able to learn new open source technologies, team up with other hackers, contribute to open source projects, and implement their own ideas into products. Most importantly, they could focus themselves on a product or a problem during the hackathon (24–72 hours) with other hackers.

The movement soon spread to other parts of the world and many more organizations. In Europe. The European Organization of Nuclear Research hosted the first CERN Webfest since 2012, and continued organizing annual hackathons till this year, boosting many open source scientific software, games, toolkits, and open libraries. In the UK, Oxford University’s OxHack and Cambridge University’s Hack Cambridge are hosted annually. Other hackathons include Hack Kings at King’s College, IC Hack at Imperial College, and many more.

The first university hackathon organized in China was Tsinghua University’s THacks in 2014. Between 2014 and 2015, Peking University, Shanghai Jiaotong University and Beihang University organized their first hackathons too. Between 2014 and 2017, there were more than 100 hackathons organized in China. In 2019, the largest hackathon in China “The 4th Industrial Revolution Hackathon” (the 4IR Hackathon) was organized in Beijing. In 2014, few developers knew what a hackathon was. By the time of the 4IR Hackathon in 2019, being a hacker had become a cool idea among Chinese developers, and hackathon became a “must-attend” event for every hacker.

Similar movements happened in India, South East Asia, Korea, Japan, Africa, and other parts of the world.

Hackathons also became a way to boost innovation within corporations. Y Combinator organized hackathons each year before the COVID pandemic and each event had a few hundred participants. In 2018, ~18,000 developers joined a private hackathon organized by Microsoft. The list goes on.

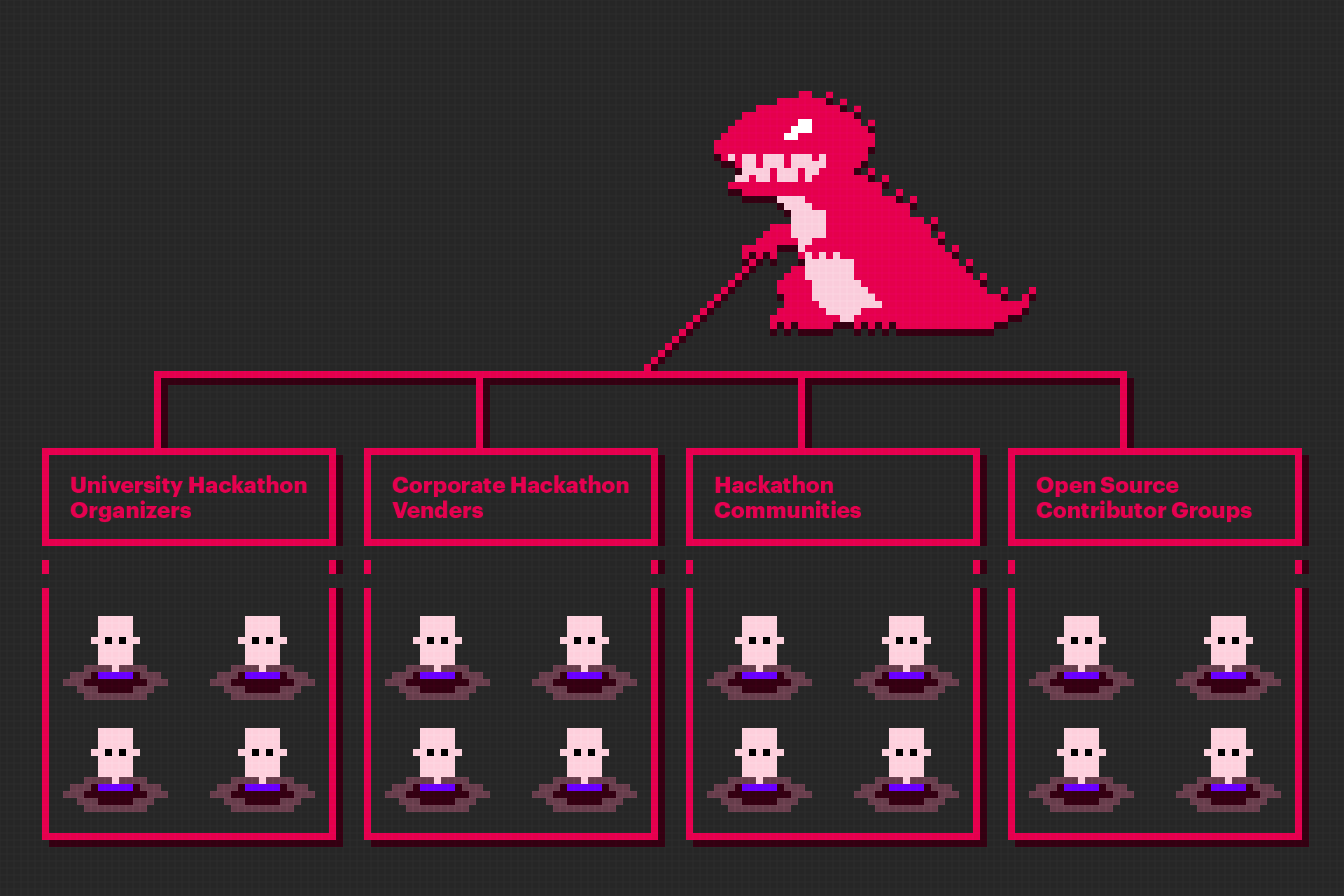

Hacker Movement Being Centralized

While the hackathon movement contributed to many interesting technologies, in the late 2010s, it became clear that the hacker movement was moving towards big companies, and further away from grass-root innovation. The Internet, as a main driver of open source innovation over the past 2 decades, became a place of monopolies. When monopolies dominate the economic interests, they also dominate the problems and ideas. Hackathon organizers rely on sponsorship dollars. When sponsorship dollars only come from big companies, and hackathon organizers struggle to compete for the sponsorships, hackathons are dominated by centralized powers.

In the process, big companies dominated hackathons and the hacker movement. The most remarkable event was Microsoft’s acquisition of GitHub for $8 Billion in 2018. One of the largest centralized tech companies acquired the most important platform of open source software and hacker movement.

While we could acknowledge many contributions made from the corporate world to the open source technologies, the open source movement and the hacker movement were created by hackers around the world, and they were made to free developers and hackers around the world from intellectual property monopolies to freely innovate.

The crypto space might have become the only sukhavati for hacker movement and open source innovation without permissions. From the time Bitcoin and Ethereum were invented to the multi-chain ecosystem we see in 2020/2021, crypto is still boosting open source innovation from all over the place.

In the Crypto and the Web3 space, Hackathons became a major place for developers to team up and innovate in the very early days. Wanxiang Blockchain Labs organized the first large-scale blockchain hackathon in Shanghai late 2015, where Vitalik Buterin presented smart contract coding to the Chinese developers. Over the past 6 years, a large number of innovative technologies and products ACTUALLY conceived or implemented at hackathons.

However, without a fundamental mechanism change, the crypto hacker communities can just become as centralized as the Internet era within the next decade.

In order to truly create a hacker community for hackers, we need to decentralize the hackathon community and the hacker movement — creating a community governed by hackers, owned by hackers, and working for hackers.

Decentralize The Hacker Movement

Can we create a permanent hacker movement to bring permissionless innovation to everyone? Can we give equal opportunities to grass-root hackers? Can we help hackathon organizers (quite often open source repo maintainers) around the world raise funding not only from big companies? Can we allow everyone who wants to organize a hackathon to have the opportunity to host one?

We will not be able to answer these questions all at once. However, we can start creating some building blocks that are critical to the goal.

The good news is — there are many available infrastructures available now to build the decentralized hackathon communities upon. There’s a lot of experience and knowledge of hackathon organizing from existing hackathon organizers to share (MHacks, ETH Denver, ETH Global, DoraHacks, etc.). Crypto-native funding mechanisms (e.g. quadratic funding) have been pioneered by the Ethereum community and widely adopted by the whole crypto space via Gitcoin and HackerLink. Decentralized governance is widely accepted by both the crypto communities and the developer communities, dGov toolkits are now widely available.

Hackathon DAO: Building A Decentralized Hackathon Community

The DoraHacks community is already supporting a decentralized community called Hackathon DAO that shares the same vision. The Hackathon DAO has already supported a USC blockchain hackathon. Nevertheless, it is worth a deeper discussion of what is needed to build such a community.

We need to build a global community of hackathon organizers. Hackathon organizers can be everywhere. Most of the time, great hackathon organizers are not “professional event organizers”, they are hackers and open source contributors themselves. The Oxford-MIT-Palo Alto-Tanzania Tele Hackathon organized by Jacob Cole in 2014 at the Oxford computer science department common room (built graph visualization technology), and the UnitaryHack organized by the UnitaryFund in 2021 (solved bounties problems for several open source quantum computing libraries) are good examples. Hackers themselves have ideas, and they know what to build. More importantly, they organize hackathons not for organizing a hackathon, but for actually building something or solving problems. By building a community of hackathon organizers, we can allow hackathon organizers in different areas of the world to connect with each other and share critical resources for future hackathons.

We need to democratize and decentralize the funding of hackathons and hackathon organizers. Hackathon hackers can be funded via bounties (for problem solving) or grants (for implementing valuable ideas). Therefore a hackathon needs funding for either bounties or grants, sometimes both. One of the most important tasks of decentralizing hackathon organizing and eventually the hacker movement is to democratize the funding of the community. A decentralized funding mechanism is important to the autonomy of the community.

We need to open source the knowledge of organizing a hackathon. Although hackathons are effective for team building and problem solving, organizing a hackathon can be a hustle. Many hackers who wanted to organize a hackathon didn’t do so because there were a lot of details to figure out, tremendously increasing the entry barrier for a hackathon organizer. A practical, open source playbook for hackathon organizers will be useful if it can lower the barrier for new hackathon organizers.

The Hackathon DAO needs community governance. With a community of hackathon organizers and contributors, there will be a lot of decision making work. Governance works might include proposal processing, DAO spending, execution team election, and maintaining the rules themselves. Proposals will be mainly about funding hackathons, as well as plans for DAO developments. With good community governance mechanisms, the community should be able to direct the DAO to grow the base of global hackathon organizers, make hackathon organizing more accessible, sustain the DAO itself, and eventually make the hacker movement an infinite game for hackers to innovate.

Related Links

- Donald E. Knuth — A.M. Turing Award

- Hackers and Painters. Paul Graham

- How To Become A Hacker. Eric Raymond

- unitaryHACK

- Microsoft Hackathon